R45 billion pain for paying Eskom customers

Between illegal “ghost” vending and municipal debt, over R45 billion in unpaid electricity costs are being passed on to Eskom customers and taxpayers every year.

EE Business Intelligence managing director and energy analyst Chris Yelland explained the extent to which Eskom’s corruption affects paying customers.

A recent probe into procurement fraud at Eskom found that scores of workers were paid over R180 million in kickbacks from contracts at some power stations.

The Head of the Special Investigating Unit (SIU), Andy Mothibi, said that R1 billion could have been stolen from Eskom.

In addition, 300 people working at Eskom were found to have financial links to companies doing business with Eskom.

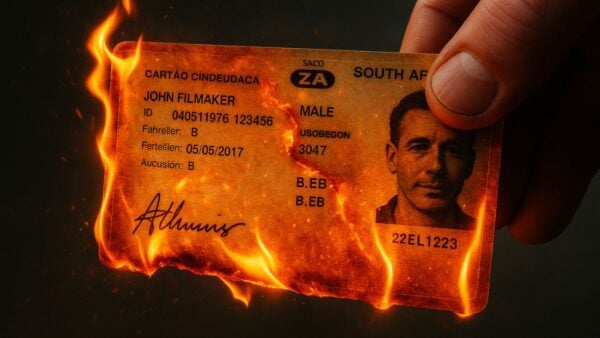

However, Yelland told Daily Investor that “ghost vending” — which entails the illegal creation of prepaid tokens, essentially allowing people to use electricity for free — is one of the biggest problems at Eskom.

“While the procurement fraud detailed at Eskom is significant and deeply disturbing, it is relatively small when compared to prepayment meter and ghost vending fraud, which has been going on for years with the full knowledge of Eskom management,” Yelland said.

“Recently Eskom announced that 1.8 million Eskom prepayment meters were not vending any legally prepaid electricity.”

A typical prepayment meter in a low-income house would normally vend about 500 kWh of electricity per month at about R2.50 per kWh.

Yelland explained that this means that Eskom is losing R27 billion every year due to counterfeit prepaid electricity tokens.

“This is the scale of the illegal fraudulent counterfeit electricity token ecosystem out there in the Eskom environment alone. It has been going on for years.”

According to Yelland, this is a result of high-level fraud at Eskom.

Eskom’s prepaid electricity systems have encryption keys which are carefully guarded and extremely difficult to crack.

However, those with high-level access within the power utility can create and sell counterfeit electricity tokens, effectively generating electricity vouchers without paying Eskom.

Yelland explained that Eskom has had the software to detect and flag meters that stop vending legal electricity.

This could be for a number of reasons, such as a meter breaking or if it is being fed illegal tokens.

Although Eskom has known how that 1.8 million meters were not vending legal electricity for a long time, the utility only announced it recently when it was performing software upgrades to prepaid meters.

According to Yelland, the reason it is only being addressed now is because — as a result of Eskom’s recent unbundling — there is nowhere left to hide this loss.

“In the past, you had Eskom as one big amorphous organization with one set of financial accounts and it was possible to hide R27 billion into Eskom’s accounts. But now, they have ring-fenced Eskom into generation, transmission and distribution,” he said.

Now, distribution — which is where this fraud is taking place — has a much lower cost structure.

“It is now impossible to hide this R27 billion loss. It stands out like a sore thumb because you’ve ring-fenced your financials to a much smaller organization — distribution.”

“Now you can’t hide it anymore. It becomes obvious to the auditors, to anybody who’s studying the financials, that there’s a hole. A R27 billion hole resulting in losses to income revenue.”

Notably, Yelland pointed out that this R27 billion number does not include non-payment and theft of electricity from postpaid meters.

For example, in Soweto, an area of direct supply by Eskom, more than 80% of the electricity delivered by Eskom is not paid for.

“Prepayment meter and ghost vending fraud are also completely separate from the non-payment of electricity purchased by several NERSA licensed municipal electricity distributors,” he said.

Municipal arrear debt to Eskom is now topping R100 billion and rising at about R1.5 billion per month, or R18 billion a year.

This means that annual municipal debt increases, and ghost vending alone costs Eskom around R45 billion every year — which the utility needs to make up for somehow.

Yelland said that, in the end, Eskom passes these losses on to paying Eskom customers by increasing electricity prices.

Last year, Eskom requested price hikes of around 36%, which was ultimately rejected by the National Energy Regulator (NERSA).

The regulator recently announced Eskom would only get a 12.7% increase in the 2025/26 financial year.

However, Yelland said that this doesn’t mean that customers are getting any real relief since if Eskom isn’t able to hike their prices, they will request assistance from the National Treasury.

“The shareholder government provides the money in the form of a bailout which comes from us, people who pay tax,” he said.

“One way or another. we pay for it. Whether we pay it in our electricity price, whether we pay for it in our taxes, somebody pays for this.”

Even though bailouts come with a set of conditions, he said that Eskom has consistently received funding despite not meeting them. As a result, the utility has no incentive to make the changes that it should be in order to fix its problems.

“Ultimately, all of the above is paid for either by paying electricity customers via excessive electricity tariffs or by the taxpayers in SA via government bailouts of about R50 billion a year,” Yelland said.

Clamping down on corruption at Eskom will be a difficult and long-term process.

“It’s not a quick fix,” Yelland said. “You have to do the right thing forever. It’s not a case of let’s do the right thing for a few years, and we’ll sort the problem out.”

This article was first published by Daily Investor and is reproduced with permission.